The general consensus seems to be that 2025 sucked, particularly among those who find themselves plugged into politics. There are wars and genocides happening around the world, pandemics (plural) raging, and a moribund economy staggering like a concussed quarterback convincing his coach he can make it one more drive. Amidst all of this, I made the peculiar decision this year to leave my fairly secure job as a regional VP of a consulting company and move back to the United States. The response I get is the same as when I tell people I’m learning Romanian on Duolingo: an instant and indelible facial expression of bewilderment and the question “why?” so extruded you can see it the italics as it leaves the speaker’s mouth. I feel guilty that I don’t feel guilty when I say that I’ve had a good year.

When you need to refactor or rearchitect a particularly complex piece of software, a perfectly valid approach is to simply turn off some features or services and see who shouts. The last few years, we watched as tech executives took this approach with their organizations, simply deleting entire teams and departments. After years of cheap capital, the entire tech industry was being bled dry. Hundreds of thousands of jobs disappeared, budgets evaporated, and belts tightened. Many things broke, but no one with any real influence screamed loud enough to stop it. It was a tough time for professional services companies and sure enough, in 2024 bony knuckles of the reorg reaper pointed at the company I moved to Germany to join.

I was naive enough to hope I would be safe. Over the last five years, I had helped build a data team from almost nothing and worked my way into a regional VP role. Despite the so-called “economic headwinds” my team produced good numbers. I was eager to work with new management and propose my ideas for how to improve a team that was already doing well. Nobody cared. I knew something had to change when I began the year by joining sales planning meetings in Chicago, London, and Bangalore and came home with world-class migraines as souvenirs. It was not a good economy to be job searching in, but every flight I entered into my tracking app felt like ripping another month off the back end of my life’s calendar.

I quit my job, telling my new boss in-person while we were at nVidia GTC. I remember how astonishingly uninspired the conference was as they fed us a stale wrap, an apple, and a bag of off-brand Smartfood for lunch. San Jose sucks, and as I walked around competitors' booths, I took photos of their nearly identical, entirely vapid slogans about how much they excel at unlocking enterprise value by harnessing complexity and executing AI at scale, whatever any of that means. I thought back to the joy I had when I studied computational mathematics and learned how to solve hard problems and wondered how that led to me standing in the background while Jim Cramer shouted from a stage on the conference floor about the world-altering benefits of AI to an audience who can’t do algebra. There are a few moments in your life when you realize that you’re on the highway to hell, and you have to get off at the next exit. This was one of them.

Already by mid-December of 2024, I had packed what was left of the belongings I had gathered in Berlin into a handful of suitcases and sold what I couldn’t for a steal to a newly-independent Moroccan woman moving into her first flat. I was exhausted from watching everything I built be stripped for parts. I had no energy for another brutal apartment search in a culturally-decaying and increasingly expensive Berlin. But mostly I missed my wife. Seven years is a long time to do long distance.

Culturally, Berlin wishes more than any city I’ve ever seen to be frozen in time. It’s a city of agelessness, where everyone eternally reaches for the aura of 1990, none moreso than the people who weren’t even born yet when the Wall came down. The problem with living in a city of perpetual youth is that you eventually grow old, and trying to stay forever young becomes indistinguishable from stagnation. On my last night in the city, I went to Olympiastadion to see Bruce Springsteen. It was my first time at Olympiastadion (despite living a fifteen minute walk away for three years); Bruce was using his European tour to deliver an impassioned plea to the world that what you see on the news isn’t all what America is. That we’re enduring a crisis but this crisis isn’t the endgame. “The American I have sung to you about for the last fifty years is real,” he pleaded, trying to convince himself as much as the audience.

I didn’t have to be convinced. I knew what America I was moving back to.

There are two problems with the current wave of AI. The first of these problems has to do with demand. In the business world, to succeed you either have to make something that people want, or you have to make something that you can convince people that they need. Pretty much every successful data science problem has involved using data and algorithms to develop a solution to a hard problem. As a career data scientist, this is what I’ve done for my entire work life, and I was lucky this year to quickly find a new job based in the US where I can continue to do just that. What makes me worry, however, is what I’ve seen emerge over the past year in the boardrooms and slide decks from the big name consulting firms that have bastardized the field that I love in a madcap cash grab.

The pattern goes something like this: CEOs report to a Board of Directors and many if not most CEOs are also board members of other companies themselves. When they all get together for their board meetings or golf dates or whatever it is they do, they’re all telling each other how much efficiency they’re gaining from generative AI. Or someone they worked with some years ago has a little AI startup and sends an email about their great new AI product. Or they get contacted by an ex-colleague doing a favor for a friend. Whatever the path, what ends up happening is these executives who know truly nothing about the day to day work of a data scientist gas each other up about the (usually extremely overinflated) benefits of generative AI. The CEO believes this, because a CEO’s job consists entirely of emails and meetings, and so when he uses ChatGPT to write an email or transcribe a meeting, he projects the tool’s ability to do his job onto everyone else’s. So he hires his tennis buddy at McKinsey to cleave an AI strategy onto the company roadmap, where it takes priority over all the other initiatives that will solve actual problems for the business. It doesn’t matter if it works or not. He has no choice, because all his board members' companies are doing the same thing. In the world of business, nothing is riskier than being an anomaly.

AI’s demand problem is that far too much of it comes from the sense of “command” and not “desire.”

If I have a sense of where we stand at the quarter century mark, it’s that everything is given to aesthetic and that not much adds up if you actually do the math. And if you don’t want to do the math, then just go out into the real world and leave your phone behind. Ken Klippenstein wrote about this recently, and it’s something I’ve been saying for a while. The saturated version of reality you read about online doesn’t comport with the vastness of the world offline. There’s a lot of bad stuff happening, of course, and it’s not my intention to minimize the very real impacts felt by people targeted, for instance, by ICE. But our world is huge and diverse and the internet is small and repetitive. When something bad happens in the news, it can be very difficult to avoid it. If ICE arrests an innocent bystander, you’ll see video of the incident for days. Or if a public figure is beset by some scandal, it captures our attention for days. But it doesn’t have to be like this.

I drove cross-country this year; I yearned to fulfill my longstanding desire to be a Jeep girl. (I joke to my wife that I had to solve one of those problems first). So I hopped on a flight to Phoenix to pick up a 2011 2-door Wrangler that I bought sight unseen, hoping it would survive a five-night dash across the country back to Virginia. Spoiler alert: it did, and I am very happy. This also let me knock something else off my bucket list: finally doing a cross-country drive, which felt as much my American birthright as anything else. I dreamed of being like Kerouac and those nomadic beat writers when I was younger—believe me when I say I was shamefully flattered when a great writer friend of mine said that the poem I wrote in January was the “Howl” of this generation, which I refuse to accept—and I wept heavy tears when I got to see the diverse natural beauty of this country.

I was ready on this trip to be defiant. I bought a big floofy skirt to wear as I drove through Texas and Oklahoma, ready to throw down with anyone who dared stop me from using a bathroom or to give me a hard time. But I encountered none of that. Instead, I found a cute queer art shop in Albuquerque, saw a barista in Amarillo proudly donning Pride wear, had a kind lady in Oklahoma tell me my skirt was caught in the door of my Jeep, and a helpful Autozone staffer in Joplin, Missouri updated my name in his computer system without a second thought. People ask if I regret moving back to the US given the way trans people are being targeted. I don’t. I have more and easier access to medicine today than I’ve ever had. I have a bigger local network of trans peers here in Charlottesville than I had in Berlin. And I have many more opportunities to advocate for trans rights here than I did in Germany.1 I’ve spent a lot of time trying to reconcile this with the anger and fear I sense online.

Of course, part of it is simply that I’m not in a position where I am deeply personally affected by the legislative assaults on trans folks. That is a privilege I enjoy and recognize. But another part of it is that I understand fascism as a politics that operates primarily through aesthetics, even as it causes real harm. (There is another argument here to be made that the harm it causes is both the means and ends of the aesthetics, that to be seen hurting people to give your audience what it demands you have to actually hurt some people.) There are, for instance, more proposed bills targeting transgender collegiate athletes than there are collegiate transgender athletes.2 The Washington Post recently ran a story about how ICE brings cameras to its raids in order to generate viral social videos, probably with the end goal of making sure Trump sees them. It’s been known for a while that Fox News is the ersatz daily presidential briefing, and if you’re a savvy little quisling in this administration, it’s more important to be seen doing the work than it is to have any impact at scale. In October, ProPublica ran a story about how ICE had arrested and detained 170 US citizens this year. Each one of these arrests is a travesty to democracy, and also if you break this down this amounts to 0.38 such arrests per state per month.

I’m not saying any of these things aren’t problems or that we can safely look away. I am saying that when you break down the numbers, they suddenly look like problems solvable by a vast and beautiful land full of 330 million people. I saw this dynamic in Budapest, where a historically large public demonstration showed up in a brilliant act of defiance of the fascist Orban regime. I believe we can do it, too. The America that Bruce Springsteen wrote about is real. Let’s just go fucking make it.

The second issue with AI, especially for the managers of all those consulting companies looking doe-eyed at ChatGPT, is that you don’t control the supply. Whenever there’s a natural disaster or a new video game console release or something like that, there’s a certain kind of dickweasel that gets it in his mind that he’s going to get to the shop early and buy out all the toilet paper or Playstation 5s or whatnot to sell at a 25x markup. The problem with these market economics, in addition to a failure to understand the modern just-in-time supply chain economy, is that these scalpers don’t control the supply. In other words, they can only control the prices so long as they temporarily monopolize the local distribution. But since they don’t control the supply, and because they bought at retail and not wholesale prices, there’s only so long that they can make that game profitable. Combined with a lack of reputational trust, a careless and greedy scalper will soon find themselves with a bedroom full of toilet paper and no one to sell it to.

AI is much the same way. Lots of technology executives eagerly want to be the ones to deliver “AI transformations” to their clients, but eventually the clients will realize that the consultancies don’t control the supply of AI, and at best they’re only able to temporarily provide a baseline level of talent to know how to use the tools effectively. For a consulting company, “supply” has long referred to the pool of candidates you can staff and sell to a client. And it will be a foolish executive who will think that they can drive margins by replacing some of this supply with AI. Because these companies rarely own the models, have access to the skills, technology and data needed to train them, and have little real world experience building them, then the only valuable supply “add” is whatever unique skills or capabilities they bring. In theory, this can be an integration, an interface, or a particular set of subject-matter expertise. In practice, the trend of the past decade to push out any sense of craftmanship in favor of tighter margins and faster delivery has ensured that few crafstpeople remain in the industry and even fewer managers know how to recognize those skills when they see them. This is why everything is so bland and shitty now. You can add ice to water to make it temporarily more refreshing but it won’t fix the flavor. When Deloitte deliered an AI-generated report full of nonsense as a deliverable on a AUD$290,000 project, the outrage shouldn’t be that they relied on an unreliable technology. It should be that they apparently didn’t have anyone a) who knew better and b) was in a position to do something to stop and ask, “what the fuck are we even doing here?”

It’s this ceaseless and wanton vacuity that inspired me more towards music and art and books and poetry this year, even if I fell short of my reading goal and barely blogged at all. There is soul in imperfection. There is beauty in friction. We have to struggle a little to appreciate anything. It is important to suffer sometimes. You have to let your favorite song move you to tears. You have to break an occasional promise.

I was ruined by Europe but still I’m glad to be from the side of the country that’s old. One of my forays into limiting the influence of the tech industry on my personal life was to write poetry; a friend organized a poem-a-day sprint in July, and while I wish I wrote anything good enough to publish, there are a few lines that spawned in my head and have rattled around for months, particularly these about how our cities take our continent for granted. I’m sharing this now in an embrace of its imperfection.

the last wild river in europe, they say,

runs its course through Albania

a land too secret and wild,

gjuha shqipe with its xs and qs

too decadent for the member states

except for the iberians, for whom decadence

is the meaning of life, and the french

for whom decadence is butter and the repose

that strident american cities yearn for

as they unfold quadratic and suicidal

into the plains and deserts

the riverbanks of europe are clean

and straight their courses only run

ragged when they are too wearied

to cover up their sandbar breasts

or when they are replete and fury

berlin buried the Panke

perhaps they got too carried away with the burying

when you run out of dead

you bury the living and

the lifegiving and

yourself

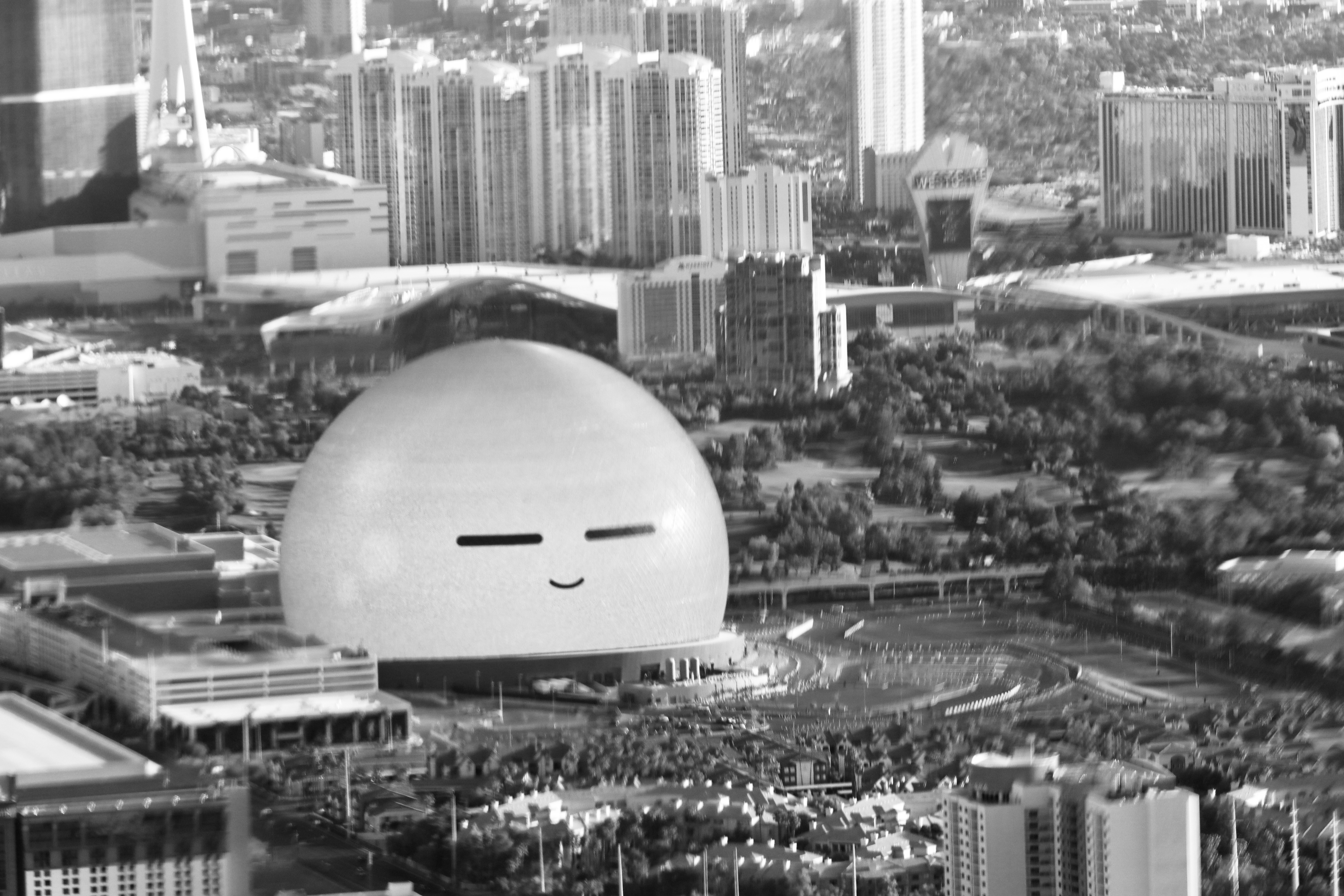

In addition to my cross-country trip (Phoenix, Albuquerque, OKC, St. Louis, Louisville), I traveled to Vegas (vapid, dying strip mall but at leat it has the Sphere), Denver (Portland with responsibilities), Chicago (great architecture), and San Jose and Santa Clara. As much as I was absolutely amazed with the nature throughout the US, I couldn’t help but feel a malaise at how these urban spaces are so antithetical to community. Our physical world keeps us separated so we go online to seek community but carry the traumas and burdens of that isolation and find ways to recreate it there. Why is politics so divisive? Because we are so divided.

One of the things I was invited to publish this year was a piece on what I hoped Charlottesville would be in 20 years. It was apparently one of the most read pieces of the year on Charlottesville Tomorrow. In the piece, I remark on how when you live in a city with centuries of history, all of your decisions have to live in a context that brings past, present and future into balance. I think it’s the question most on my mind right now. What do we owe to our ancestors? What do we owe to our descendants? And what do we owe to ourselves?

I’m getting older now. I’ll turn 44 in 2026. I’m probably at the midpoint of my life, if I’m lucky. I felt like transitioning in my 30s gave me another decade of youth, but I am paying that debt now. If I’m having a midlife crisis, then it is manifesting is through the desperate quest to make memory and experience worthwhile. And so, in a year filled with fear and uncertainty and crisis and catastrophe I found ways to fill it with music and travel and family and love. In a poor attempt to keep memory worthwhile, I’ll leave you with my favorite photos I took this year.

2025, at least:

- 31 cities

- 15 states

- 11 countries

- 48 books read

- 30 poems written

- 1 publication

- 3 citations

- 2 podcast appearances

- 20 successful physical therapy appointments

- 3 goals scored

- 1 new job

Posted: 31.12.2025

Built: 02.03.2026

Updated: 31.12.2025

Hash: 073bcaf

Words: 3287

Estimated Reading Time: 17 minutes