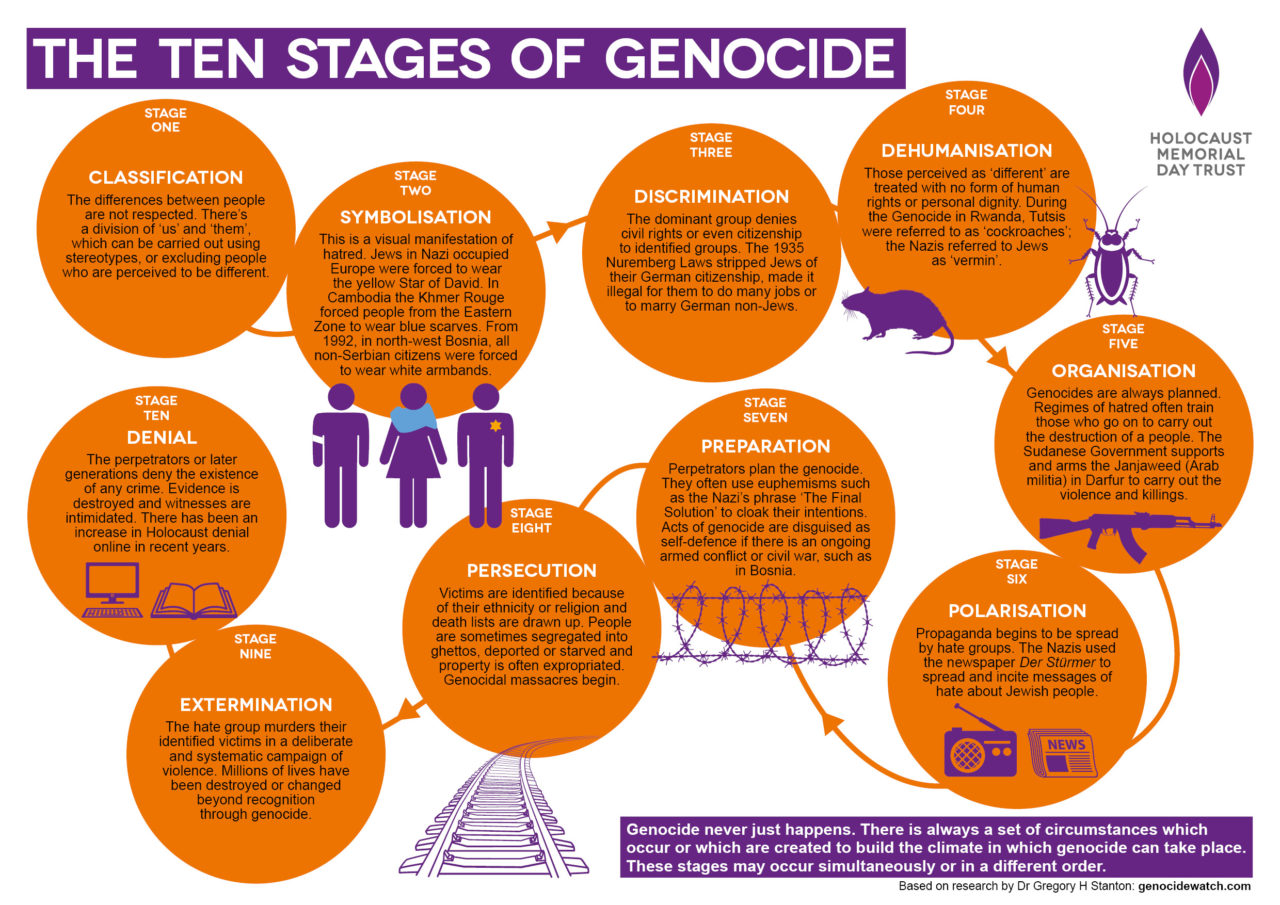

You’ve probably seen the image before. It’s a clever infographic, sometimes presented as a list, or sometimes presented as a meandering path through ten stepping stones, elaborating the “Ten Stages of Genocide.” This is a popular image in Holocaust education, and one that has been used effectively to describe the path to the Holocaust in Nazi Germany. It’s an image that fits nicely into a meme, which gives the viewer enough details to feel informed but not overwhelmed. The problem is that it’s also completely misused.

The Ten Stages of Genocide model comes from Gregory Stanton, a former resesarch professor at George Mason University and the founder of “Genocide Watch,” a think-tank studying global conflict. Stanton’s model proposes that Genocide occurs in ten stages, ranging from Classification to Denial, with stops in between leading from Discrimination to Killing. It’s easily digestible, and it’s easy to point at it with a “you are here” sign as a sort of alarmist way of calling attention to civil rights issues and the risk of future atrocity. Since 2017, I recall seeing it float around social media with various contexts, first to describe the treatment of the Trump Administration of Muslims, and later of immigrants at the southern U.S. border. Lately, it’s being shared as a callout of the various state-level proposed legislation winding through American statehouses.

Yet despite its recurring popularity, often presented alongside variations on the Niemöller poem (which rarely acknowledge that two years ago we were saying that some other group fits the pattern “first they came for the…"), I’ve seen comparatively little critique on the model. This doesn’t mean this criticism doesn’t exist.

Among genocide scholarship exists a subfield of “critical genocide studies,” which seeks to reflect on both the means and motivations of a field with little governance or accountability. Genocide scholar A. Dirk Moses wrote in 2008, “[t]he inability of Genocide Studies to predict or interdict genocides is a problem (Moses, 2006) and it is worthwhile considering why. Constituted mainly by social scientists from North America, the field has been dominated by the nomoethic approach that seeks hard knowledge in the form of universal laws with predictive potential.”

The genocide scholar, Professor Henry Thierault, recently addressed Stanton’s ten-stage model more directly:

First, the “stages” of genocide assume genocide happens in a consistent and teleological manner that defines it. But even a shallow examination of any reasonably large set of genocides shows that this is not the case. The stage approach is actually what I will call a “backwards teleology,” that is, produced by working in reverse from a completed genocide. By working backwards, a supposed causal sequencing magically appears. The problem is, there are genocides that have not followed anything close to the pattern claimed, while there are many non-genocides that have included many of the stages indicated, even extermination. The latter means that there are many false negatives: imminent or even accomplished genocides do not register as such according to the “10 stages” approach…. The “10 stages” approach is completely unscientific. The only way it could be established scientifically is if the “10 stages” method were shown to apply only to genocides as well as necessarily to genocide; but the facts show neither of these are the case. This exposes a basic logical fallacy in the inference from all or some of the “10 stages” to the claim that genocide is happening or imminent.

Thierault’s critique claims that the linearity of Stanton’s model reduces genocide to a simplified grand narrative. To Stanton’s credit, the linearity assumption need not strictly hold. Nevertheless, as the infographic above shows, it quite clearly presents genocide as an escalating and unidirectional model. Thierault also addresses the problem in reverse, providing a useful analogy:

Blood is a red liquid that dries when exposed to low-humidity air. Wine can also be a red liquid that dries when exposed to low-humidity air. The fact that we observe a red liquid drying in low-humidity air does not justify our asserting that the substance is blood, any more than the occurrence of all or some of the “10 stages” determines that an event is genocide. This reflects another basic logical fallacy. Thus, the “10 stages” approach leads inevitably to false positives.

Put more simply, it can be that all ten stages in Stanton’s model can be met, and yet genocide does not happen (per legal definition or otherwise), and it is equally possible that genocide does happen without all of the stages being met. This means that the model lacks both predictive and explanatory power.

Other recent efforts have tried to build stronger predictive models for genocide. In her book On the Path to Genocide which explores the Rwandan and Armenian genocides of the 20th century, Deborah Meyerson explores the difficulty of the stage models to explain genocide, emphasis mine:

[E]xamining constraints that inhibit genocide is crucial to developing our understanding of the aetiology of the crime. For genocide to occur, not only must certain risk factors be present, but inhibitory factors must also be absent.

Inhibitory factors have received far less study and analysis that risk factors, and they would be much harder to present in a pithy infographic. Addressing these challenges, Meyerson presents a temporal model of genocide whith eight stages that attempt to account for conditions that can work to slow or prevent genocide from occurring. These factors, which I reproduce here, are:

- The presence of an outgroup. This can be defined as a relatively powerless minority, with whom relations are politicized, and which is subject to legal discrimination.

- Significant internal strife. Significant, ongoing destabilization that affects the dominant group and the outgroup, and for which there is no clear solution.

- The perception of the outgroup as posing some kind of existential threat to the dominant power.

- Local precipitants and constraints determine the nature and time of the dominant group’s response. A violent response is typical, with the onset of massacres quite likely.

- A process retreat from the intensity of the circumstance, or further escalation. While the process is commonly one of retreat, repeated cycles of escalation through the proceeding stages followed by retreat ultimately facilitates further escalation.

- The emergence of a genocidal ideology within the dominant pwer, typically accompanied by concerted efforts by the dominant group to further augment their power, and a deepening perception of the outgroup as posing an existential threat.

- An extensive propaganda campaign, a key component of which features attempts to present the victim group as a grave threat to the dominant power.

- Case-specific precipitants and constraints determine the precise timing of an outbreak of genocide.

What’s interesting about the temporal model is that it compares the Armenian genocide, which predated the risk models by several decades, to the Rwandan genocide, which commenced after many such models had been published. Therefore, these cases offer a sort of “control” by which the predictive or descriptive power of the earlier models can be evaluated.

Meaningful study of inhibitory factors is harder to find; in his Ph.D. thesis 12 years ago, William Pruitt performs a qualitative comparative analysis that explores five factors using four dichotomous variables: autocratic governments vs. democratic governments, socially-constructed groups present vs. absent, high vs. low individualization, collectivisation present vs. absent, and triggering catalysts present vs. absent. In his analysis of seven cases, all cases shared in common that they had autocratic governments with socially-constructed groups present. Emerging from this analysis, one might infer that social diversity and functional democracy are strong genocide inhibitors. These inhibitory factors are missing from the popular ten-stage model, which conflates their absence with the presence of risk factors. From the perspective of avoiding and preventing genocide, perhaps the attention should be in the reverse; rather than avoidance of risk factors, perhaps we should position for the strengthening of inhibitory factors.

An understated and often overlooked aspect in the critique of genocide studies is the western, largely North American focus on the field. Stanton’s call to action on Genocide Watch includes “the establishment of a United Nations rapid response force in accordance with Articles 43-47 of the U.N. Charter.” Calls for early warning for and early intervention against genocide are often coupled with a neoliberal attachment to policing and militarization, yet the interventions almost always come too late, after the genocides have been underway (e.g. Bosnia, Ukraine). There is a lack of self-reflection in the scholarship, as the calls to public education of genocide often focus on genocides in the developing world presented as internecine conflicts between ethnic groups, and rarely affords developed, industrialized nations the duty of historical retrospective. The analyses of genocides therefore rarely include the escalatory risk factors present in the colonial genocides of the western powers, or the ongoing persecution of indigenous people by favored nations.

The presentation of the current struggle for transgender rights as an ongoing or imminent genocide is therefore problematic on two fronts: first, it relies on flawed models that lack predictive accuracy or stopping power, and second, it leverages models that whitewash genocide as something that morally compels the policing power of the (white, western) savior nation.

Even if we ignore these critiques, Stanton’s model is misapplied in the current framing. Stage Two of the model, Symbolization, says that outgroup minorities are compelled to identify themselves. The opposite is the case in America, where current legislation seeks to prevent people from identifying themselves. Likewise, Stanton’s Stage Five, Organization, describes the early phases of organized killings, often with the tacit or implicit support of a regime. As bad as the Proud Boys are, they have not engaged in systematic killings of transgender people in America, and while anti-transgender violence is rising, including murders, these still fail to rise to the level of killing that we see in early-phase genocides around the world.

Applying the temporal model presented above, we can see that the situation is quite a bit farther from imminent genocide. While transgender people are being targeted and persecuted by hateful laws, and while we are victims of hate crimes at an alarming rate, we do not have “significant, ongoing destabilization that affects the dominant group and the outgroup, and for which there is no clear solution.” And while many column-inches have been spent on the death of American democracy, the reality is that the many hundreds of anti-LGBT bills introduced in the last several years have been effectively killed by democratic processes, and many of those that have become law have been stopped by the courts. It is difficult to argue in the face of the evidence (Texas killed 75 of 76 anti-LGBT bills in 2021!) that America has shifted into a strong autocracy, as Pruitt’s model would require. The opposite appears to be true: the Democratic party had a historically strong mid-term performance in 2022. Analysis of multiple models of genocide paint a vastly different picture than the infographics we spread around Twitter.

Genocide is a big word. Not every civil rights struggle becomes a genocide; not even every war becomes a genocide. In many cases, societies at high risk for genocide, including those which met all ten stages of Stanton’s model, including killing, did not fall into genocide. It is difficult to describe the magnitude and scale of genocide; I saw it myself when I drove into the Ukranian border checkpoint at the start of the war and saw a level of human suffering and resilience that I never before understood. Not all bad things that target minorities are genocides, and even when some of what is being proposed in America bears superficial similarity to genocidal behaviors, this does not make them genocides.

When the Polish lawyer Raphael Lemkin defined the term “genocide” to as a legal term to describe the Holocaust and similar horrors that came before it, he defined eight factors of genocide. These include factors such as ethnic, religious, and language differences between groups. While not all of these factors need to be present, and in fact the United Nations' definition is more limited, it’s hard to apply most of them to the current context in transgender rights. By way of example, transgender people do not speak a different language from the dominant group as a general rule; if they do, it’s usually for reasons other than the fact that they are transgender. Simply put, there’s no known hereditary element to being trans, and in fact this is a crucial difference for why we admit that people can be transgender, but not transracial. A transgender person is not necessarily born to transgender parents, although if they are, maybe they have an easier time coming out. The converse also holds. This is relevant in the analysis of genocide in both a legal and cultural context.

For instance, the horrific proposed legislation in Florida that would remove children from households of transgender parents appears to meet genocide condition of forcible removal of children. Yet this differs in key ways. First, this is a criteria of genocide when it is done to erase ethnic identity by reducing populations. This is not true in the case of taking kids from transgender parents: the children of transgender parents are not necessarily transgender themselves, nor would removing them to foster care make them more or less likely to be transgender. Second, there are cases of the state removing children from parents, for instance when parents have substance abuse problems. This is a forcible removal of children, yet we do not consider this to be a genocide of alcoholics. Of course, saying that this proposed law isn’t genocide is not an endorsement of the bill; something does not need to be the worst thing in order for us to decry it.

I suspect that the invocation of the term “genocide” is done as an attempt to beg the attention of the apathetic, that by caring about our struggle, perhaps we won’t have to struggle. Yet the track record of genocide studies here paints a bad picture. The call to attention of actual genocides around the world has rarely resulted in timely policing or military intervention. Simply put, the word does not have the shocking or staying power we hope it to have, even in the case of widely documented ongoing atrocities. It’s not likely to have any similar rhetorical effect to compel action to a civil rights struggle where the level of killing is still several orders of magnitude lower than what is happening elsewhere in the world. The average American remains only superficially aware of genocides of Rohingya, Uyghur, or other peoples in the world, and what opposition exists may even be motivated by a sense of moral, political, or even racial supremacy. There is a distinct element of white privilege present in the invocation by largely white American transgender women of the word “genocide.” It is true that everyone is entitled to their own feelings and reactions to trauma, and that intersectional analyses should refrain us from engaging in oppression olympics. But genocide is worse. It is worse on every measure and every axis, by a staggering margin.

Using the word “genocide” to describe the current struggle is not only misleading, it may actually be harmful. Spreading a message that transgender people are on the brink of an imminent genocide is not a message that sends hope for the future. And the more transgender people that feel like their deaths are imminent, the more they look around and see a society that is not organizing to stop these deaths, further reinforcing the feeling of helplessness. The worse things seem, the easier it is to demand explanation for why the others aren’t doing anything. This is a dangerous spiral for a population that is already at increased risk for self-harm, economic insecurity, and substance abuse.

The central problem with using a flawed and simplified model to define the current situation as an imminent genocide is that the model provides no guidance for active intervention. Stanton’s own organization calls for U.N. policing and military intervention to stop genocide. The United States is not a society with a capacity for self-organizing to stop mass killing (and, of course, there are no plausible indicators that organized mass killing is imminent). The solution to a Republican politician introducing proposed anti-transgender legislation is not to take that politician out back and shoot him nor is it to have him arrested; it is to organize to stop the bill in subcommittee, committee, the general assembly, or at the governor’s desk. The solution to the current state of affairs is a civic remedy, because the current state of affairs is a civil rights struggle, and not a genocide. And while things may get even worse for trans people in America, the efficacious solutions still appear to be things like internal relocation, legal aid, and organized direct action; responses more commonly found in active civil rights struggles than in societies under threat of genocide.

The thinking goes that if genocide is to be prevented, it must first be predicted, and it is an alluring belief that a simple model built on historical wrongs can neatly and flawlessly predict genocide in such a way that it can be stopped. Less attention is paid on how precisely the genocide is to be stopped, and what the costs of a false positive or false negative could be. If the political fate of a people could be reduced to a simple ten factor model so simple that it fits into a meme, then we would have a far easier and safer world. Alas, these ideas traffic well but do very little, serving more as mythologies of neoliberalism than proactive or productive ways to secure human rights.

The demand to respond to impending genocide is a futile call to action if only because of the terrible historical track record of stopping genocides. It relies on a flawed model that implicitly calls for more western policing and hegemony and draws focus away from more effective, targeted calls to action. Simply put, there is almost nothing that someone can do in the face of an early warning alert for genocide, but there are many things that people can do to support a growing civil rights movement. Our energies are probably better spent not raising a shocking alarm, but by constructively organizing a multi-layered and escalatory approach for demanding our civil liberties, starting with legislative lobbying and rising to include many forms of direct action. As the war in Ukraine continues and mass killings take place in various corners of the world, it’s hard to convince anyone the current round of anti-transgender legislation rises to that level. A stronger appeal must include a more realistic and grounded language, and ideally one with a stronger track record of success. But most of all, we owe each other better than to spread the despair of our imminent deaths. We can and will beat back the wave of hateful legislative assaults.

Posted: 08.03.2023

Built: 24.02.2026

Updated: 24.04.2023

Hash: af511b0

Words: 3180

Estimated Reading Time: 16 minutes