The first trip

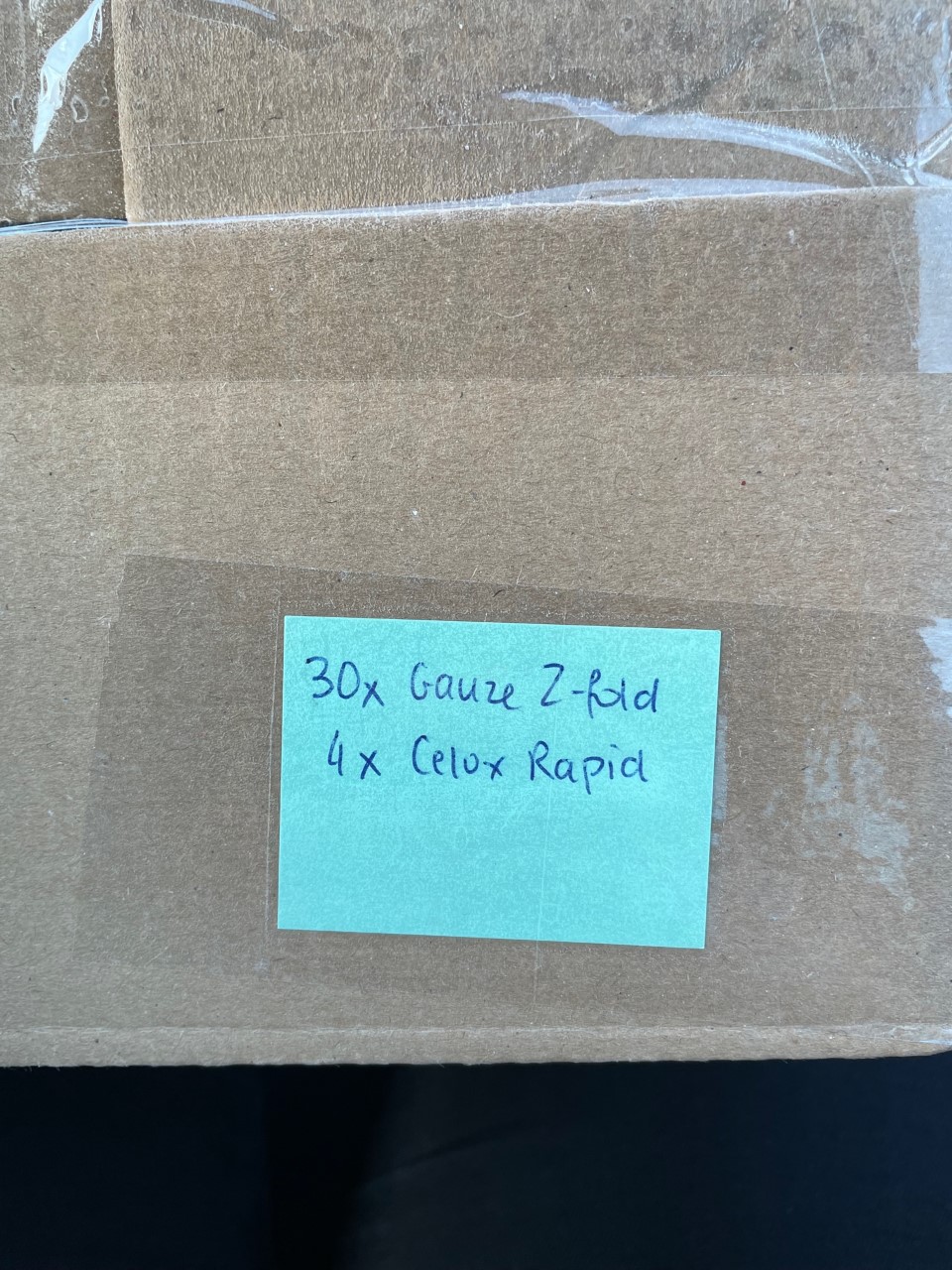

Yuri1 waited for us in the driveway of a bistro in a suburb just outside of Łódź. A Ukrainian doctor sporting a tracksuit and a three-day shadow, he was nearly in tears when my co-driver, Ines and I arrived. We brought with us a package we had acquired earlier in the day in Warszawa, a box of Celox z-fold hemostatic bandages, a type of advanced bandage that can stop bleeding from a gunshot wound in just a few minutes. Yuri had spent his entire day gathering badly-needed and hard-to-find medical supplies all over central Poland, and was heading to the southern border crossings the next day. On the verge of exhaustion, we handed him a bottle of water and parted our separate ways, him heading east, and us heading back west. “After I met you, I believed that this world still has a chance. You are completely not involved to this shit, but nevertheless helped us… Thank you for that,” he texted later. There is a kind of life you live before a Ukrainian doctor from Kharkiv gives you a bear hug before heading off to a war zone, and a kind of life you live after.

Since the first weekend of the renewed Russian war in Ukraine, I’ve made two trips from Berlin to the Ukrainian border to deliver humanitarian aid. For the first of these trips, I connected with Ines, who had been organizing an early shipment of relief supplies from her home in the Netherlands. She started the #DriveForUkraine hashtag in an effort to raise awareness for the plight of war victims, soliciting humanitarian supplies and donations during the first days of the war. We connected on Twitter and when I saw that her planned route took her just south of Berlin, I offered to be a co-driver and try to drum up some more support among friends in Germany. I wrote my best friends, Em and Pao, to see if they wanted to join, and they rented a minivan and planned to join us on an impromptu three-day mission to the Ukrainian-Polish border.

In Berlin, the shops are closed on Sunday, so after hastily organizing everything, I ducked out Saturday to run to Ikea with a plan to buy as many blankets as I could find. Pro-tip: the Ikea Silvertopp blankets measure 140x200cm and are rated medium-warm, cost only 6€, and are tightly rolled for easy transport. Our mission for this trip was simple:

- Deliver humanitarian relief where it could get to those in need;

- Bring marginalized evacuees who may not feel safe in shelters in Poland and bring them to Berlin;

- Forward financial support on to those in need.

On Monday we set out and made it to Poznań, a city only four hours from Berlin, but ten hours from the Netherlands, where Ines had departed after loading up her car that morning. We distributed our relief supplies between Ines’s car and our rental minivan, loading both up to the point where we could only barely safely see out the windows. In Poznań, we noted how distant the war still felt. There were few signs of anything out of the ordinary. We walked to Stare Miasto for dinner as people were leaving theaters and social engagements. Life felt normal. The next morning, the only sign of war was the non-stop coverage on the TV in the hotel lobby.

With a destination still uncertain, we set our GPS vaguely in the direction of Zamość, stopping to load up on still more humanitarian supplies as we left: power banks, batteries, and cables. As we headed east towards the border, the war became increasingly present. Huge lines of tanker trucks, presumably carrying fuel, were an endless presence along the highway. Interestingly, many of these tanker trucks had signs indicating a flammable load, but the words “NUR FÜR LEBENSMITTEL” on the side, a German phrase that translates basically to “foodstuffs only.” I wondered if milk tankers had been converted to carry petrol for the war effort, if such a thing was even possible? I am aware of very few flammable liquid foodstuffs that commonly transport in tanker trucks.

As we were about an hour away from the border, I noted the presence of high-altitude contrails in the sky headed east. “Those have to be military planes,” I remarked. “Nothing commercial is flying into Ukraine.” Sure enough, we soon saw military transport planes circling the skies, presumably delivering lethal and/or medical aid into Ukraine. A pattern of racetrack contrails belied what I later discovered to be an RC-135 electronic surveillance flight along the border. The feeling of war was unmistakable now.

Ines had drummed up a lot of media attention in the Netherlands, and using her connections with some Dutch news stations, we eventually identified a depot in Rzeszów that was collecting supplies to head inbound to Ukraine. We arrived that night just as they were loading a coach bus headed for the border. A bucket brigade of Polish volunteers helped us get supplies from our car into the bus, of particular importance were our medical and electrical supplies. There was, and still is, a massive need for medical aid as well as power banks, chargers, and cables. At the depot, behind a few sets of doors, young people, were performing military drills. Whether they were preparing to defend Poland against a future threat, or preparing to ship off to Ukraine to defend against the present one, I do not know.

Information was and remains extremely hard to find among English-language sources. There is an immense amount of confusion about where supplies are needed and which supplies are needed. It’s not always clear which shelters are providing support for evacuees in Poland, or forwarding support on to Ukraine. The response is currently overwhelmingly being driven by grassroots organizations; while some NGOs like Deutsches Rotes Kreuz are evidently supporting at scale, the overwhelming support we have seen has come from independent groups from all over Europe doing direct outreach and networking. In many cases, this is much more effective, even if it isn’t as scalable. With these groups, we can guarantee we are getting the aid to people who need it, and who often fall through the cracks in what NGOs support.

After dropping off supplies in Rzeszów, we set out seeking shelter. All local accommodations were booked, and though we had planned to sleep rough if needed, we did find some space in a hotel in Lublin, two hours away. We booked a couple of rooms and headed there for the night. The next morning, some evacuees were trying to check in early at the hotel, and we offered to pay their rooms for a few nights using the funds Ines had raised, which they gladly accepted.

Our primary mission complete, we focused now on the secondary mission to bring people back to Berlin. Though we knew tons of people needed a ride, we were having trouble finding solid, verifiable information as to which depots needed the most help, and we had no success connecting with LGBT groups. One network didn’t understand our request. “But men are not allowed to leave,” we were told, as if the only LGBT folks were men. By far the biggest challenge at that point was still getting people out of Kyiv, Kharkiv, and other cities under attack.

Pao had some connections in Warszawa, however, so we headed there for some food, rest, and regrouping. At this point we split up, two of us would go pick up a pair of Jewish teenagers and an Ethiopian Muslim woman who made it to Warszawa, and two of us would collect the medical supplies to deliver to Yuri, waiting in Łódź. After a successful day driving all over Poland, we eventually got everyone and everything to where it needed to be, and set back off for a long drive back to Berlin.

The second trip

Fresh off the first trip, I watched closely as the situation at the border became increasingly desperate and saw tons of bad information floating around. Berlin has a public holiday on March 8 to celebrate International Women’s Day, and I had already scheduled Monday the 7th as a day off. Originally, I had planned to go to Italy for a long weekend, but there were more important things to do.

I connected with a volunteer startup in Berlin on Telegram that was planning a relief convoy and volunteered myself as a co-driver. The group was better organized than we were in our first trip, and they had been collecting supplies at popular locations in Berlin throughout the week. Our mission was clear: two cars would bring volunteers to Przemyśl, and two vans would bring medical supplies, including defibrillators, hemostatic bandages, syringes, hand sanitizer, and more directly into the “neutral zone” between the Polish and Ukrainian border checkpoints, transfer them to a depot or another handler, and come back out. This was a little bit riskier than the earlier plan, as it involved actually driving into Ukrainian territory, but there were plenty of similar stories from other convoys where this exact exchange went off without a hitch. The plan was clear: meet on Sunday midday, drive to Przemyśl, arrange for who would be driving into the controlled zone, and spend the night in the shelter set up for volunteers.

Unfortunately, those plans fell apart pretty quickly, as plans tend to do. After we were well en route to the border, we learned that passports were necessary to enter the neutral zone, and European ID cards would not suffice. Of all of our drivers, I was the only one who was in possession of a non-Russian, non-Ukrainian passport. That meant that to deliver the supplies, I would have to drive in alone, come back out, get the second load, and drive back in. No problem, I thought. We had support from the Ukrainian delegation in Berlin, and there should be no problems getting the supplies through.

We arrived around midnight to the Korczowa-Krakovets border checkpoint. I dropped my co-driver at a nearby hotel and took his van into the checkpoint. Pretty soon I realized that the plan was much different than I envisioned. As soon as I crossed the Polish checkpoint, I realized there was no “neutral zone.” I would have to drive through Ukrainian passport control and customs and into Ukraine to deliver the aid. Alone. After midnight. With poor cell service and no translator until after customs. There was no turning back.

Getting through passport control and customs was easy. There were a few other vans there also delivering aid. After the customs control, I met our Ukrainian contact and transferred the goods to her truck. As I left, I ended up behind two other German relief vans. They were let through. I was not. “Poland is closed” they told me.

I was now stuck in Ukraine. Alone. After midnight. During a war.

I got back in touch with my contact and she helped negotiate my transit. “Drive back the way you came,” I was told.

I did that, and the Polish border guards told me that I couldn’t go that way. So I went back to the customs house and asked for help again, typing into Google Translate. “Drive up to the roundabout and come back in with the other cars” they told me. So I tried that, and was stopped by a soldier who told me to go back the way I came.

Everyone I interacted with told me something different and wrong. One Ukrainian soldier was getting quite frustrated with me, understandably, but there was nothing I could do. Eventually, I found a guard who told me to use the gate behind the customs house. Ah hah! I had not seen the gate, because a bus had been parked in front of it. Eventually, he would come by to open it, and I was able to safely cross back into Poland with the large line of evacuees. Altogether, this took me around two hours in the middle of the cold, snowy night.

The border crossing is difficult to explain. Group after group of women and children were being directed through my side of the customs control and sent into Poland, where they were received by border guards offering water, food, and warmth. It was quiet and calm the whole time, none of the children were crying or complaining, nobody seemed to be panicking or losing control. Despite their obvious frustrations with me, which I definitely deserved, the border guards in both countries were unfailingly polite and helpful. Despite being stuck literally in a war zone, I didn’t really feel unsafe, I was mostly worried about having to overnight in the back of the van with only a flimsy sleeping bag for warmth.

After getting out, I met back up with the group and we decided to transfer the second load to someone in Przemyśl, and we headed off for the long drive back to Germany.

What I learned

In brief:

- The situation changes hour by hour and it’s nearly impossible to know who needs what and at what time. You have to plan for flexibility.

- Grassroots movements are greatly outpacing NGOs in providing targeted aid and it’s not even a close game. NGOs are having trouble getting supplies into Ukraine.

- Some people have been saying to stop sending supplies because the shelters are full. This isn’t true. Clothes aren’t needed, but medical supplies, power banks, cables, warm socks, and more are still needed as of this writing. This may change by the time you read this.

- Most evacuees seem to be confident they will be able to return in weeks or months, not years.

- A lot of people are falling through the cracks: Muslim evacuees, third-staters, LGBT folks, and so forth. These people need the most help.

- The mobilization has been remarkable everywhere we’ve seen it. Massive volunteer areas set up in empty areas of Berlin Hauptbahnhof. Convoys of supply vans and passenger busses from all over Europe.

- The volunteer shelter in Przemyśl is absolutely not suitable for volunteers to sleep in.

- There was a run on gas and some stations along the highway were out. Others were out of cash.

- I really don’t recommend doing a neutral zone run unless you have to or unless you speak Polish, Ukrainian, or Russian. It’s complicated and risky.

What comes next

I doubt I’ll make another border run. It’s a three-day commitment and I can’t keep taking time off to make those trips. Instead, I’m taking in a Ukrainian family using my guest bedroom, and using my time to volunteer at Hauptbahnhof wherever I can. This war has created an immense humanitarian crisis and while it is true that standing around and getting in the way is worse than doing nothing, people still need volunteers, drivers, coordinators, translators, and money. Donate your time, your body, or your cash in some way!

-

Names changed to protect the innocent ↩︎

Posted: 09.03.2022

Built: 26.02.2026

Updated: 24.04.2023

Hash: af511b0

Words: 2524

Estimated Reading Time: 13 minutes