The first book in the series is The Turmoil, written in 1915. Tarkington grew up in Indiana during the Second Industrial Revolution, a period characterized by rapid growth and heavy migration, in a country expanding faster than its means to control such expansion. Every boom period is followed by a bust, and Tarkington’s works seek to capture some of the human elements of this characteristic of capitalism.

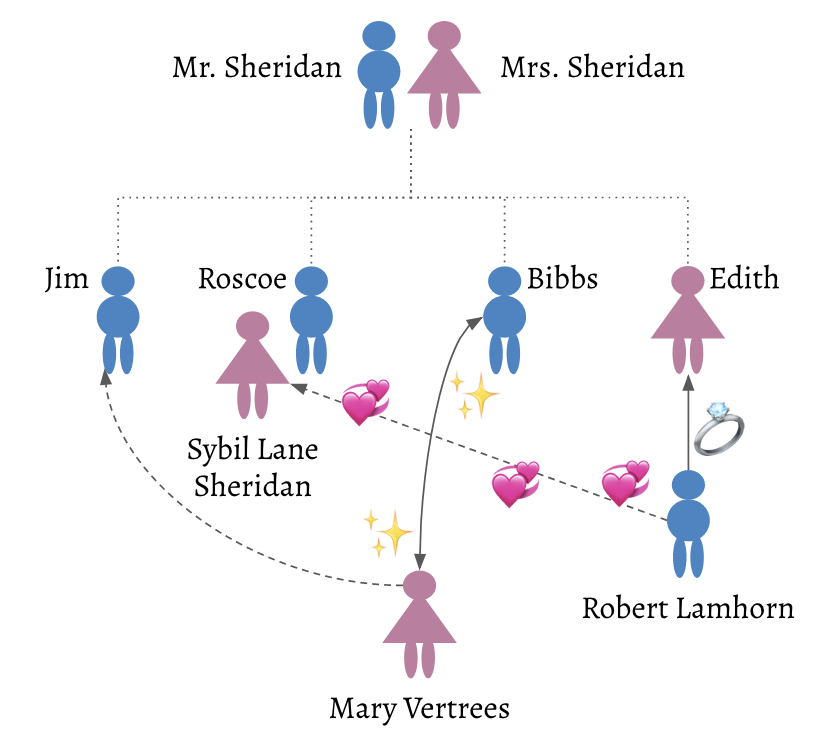

Published in 1915, The Turmoil foretells the crushing bust that would soon affect many mid-sized Midwestern cities. The story follows the Sheridan family, a new-wealth capitalist family that rose to the top during the early industrial expansion in an unnamed but prototypical Midwestern city. Led by Mr. Sheridan, a powerful but mediocre patriarch, the Sheridan family consists of Mr. and Mrs. Sheridan and their four adult children: Jim, Roscoe, Bibbs, and Edith. Bibbs is the family’s black sheep. Sickly and frail and anxious with dreams of becoming a writer, Bibbs is forced by his father to work on the factory floor.

Tarkington’s novel serves as a capitalist retelling of the story of Job. Tarkington’s characters are one dimensional; that one dimension is little more than a vessel to convey the story of the trial of Sheridan’s (Job’s) faith in capital (God). Sheridan is beset by a series of maladies: Jim dies in an construction accident brought on by unregulated corner-cutting; Roscoe discovers his wife is having an emotional affair and falls into a state of non-functioning alcoholism and quits the family business; and while trying to “teach” Bibbs how to use a machine that he is absolutely unqualified to use, Sheridan manages to cut off the tips of several fingers, leaving his hand mangled. Meanwhile, Edith leaves for Florida and marries Robert Lamhorn, the man who had been emotionally cheating with her sister-in-law, Sibyl.

Bibbs befriends Mary Vertrees, the daughter of the old-wealth family whose riches are rapidly dwindling. Initially courting Jim before he died, Mary and Bibbs grow close. Mary invites Bibbs over to watch her play one night, coyly avoiding mention that the family piano will be sold in the middle of the night. Bibbs’s physical and mental health improve as they get closer—and as Bibbs falls in love. Finding a rhythm in the machine shop, Bibbs engages gently with socialism and spends his spare time writing poems about his newfound friendship with Mary.

Mary’s character is as one-dimensional as the rest. She is little more than 1915’s version of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl trope; Bibbs, the flawed male sympathetic protagonist. Mary exists merely to provide Bibbs a way to heal and to discover his competence and confidence. When it is revealed that Mary’s interest in Bibbs may not be genuine, he abandons his whimsy and burns his writing. Bibbs accepts his father’s offer to take an executive position in the company, replacing the wayward Roscoe. Bibbs succeeds in this role, and quietly and anonymously purchasess the Vertrees family’s valueless stock for an absurd sum. Mary, unaware of the purchase, sees Bibbs nearly run down by a car and re-connects with him in Bibbs’s penthouse office in the city’s tallest building.

Sheridan’s faith in capital is rewarded, and thanks to the sacrifice of a woman whose role in the story is nothing more than to make a man whole, Sheridan’s success is guaranteed to live on through his unlikely son, Bibbs.

The Turmoil is filled with the toxic gender roles typical of the time. Mr. Sheridan is a token of mediocrity. His tastes in art and home decor are tacky and outdated. His self-confidence is at odds with reality; his perception of reality is distorted so that everything he likes is Good and everything he dislikes is Wrong. One might be willing to say that Sheridan is a prototype of Donald Trump.

The novel also touches on the environmental calamity of the time. The city, beset by the dust, smoke, and grime of rapid industrial expansion, is often portrayed as filthy and unhealthy. Sheridan views the smoke as a symbol of greatness and growth, dismissing townsfolks' concerns about its harmful effects. Gaslighting the community, Sheridan tells concerned citizens that the smoke is what gives them their paychecks, that they ought to be grateful.

When Bibbs engages with communist and socialst ideas on the factory floor, it seems as though the novel may serve as an open challenge to unchecked capitalism. And when Bibbs is presented as a sickly character with feminine interests, Tarkington manages to hint towards a rejection of the American masculinity

Ultimately, the novel fails on both fronts. Capitalism is saved by the acts of a capricious and enigmatic woman who exists only to heal the troubled man, who steps in to provide Sheridan with a remedy to his tormented ailments. The only hint that the rest of the Growth trilogy may not be full of such apologetics is a parting scene where Sheridan, removing the bandages from his industrial accident, reveals a permanently mangled and disfigured hand, a reminder of Capital’s omnipotency. We can see in this story much of what we see in the world today: declining wages, ecological crisis, and the unchecked power of a talentless demagogue. Unfortunately, the story gives its reader little hope that those patterns of history will be avoided this time around.

To read more about my Modern Library project, read this post.

Header image: Pixabay

Posted: 28.12.2018

Built: 25.02.2026

Updated: 24.04.2023

Hash: e3829a8

Words: 985

Estimated Reading Time: 5 minutes